In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kerala was a region alive with diverse communities, languages, and religions. Despite this vibrant cultural mosaic, everyday life was overshadowed by deeply rooted social hierarchies. The rigid caste system allowed practices like untouchability and widespread discrimination, keeping lower-caste communities away from education, fair economic opportunities, and social privileges.

Narayana Guru (1854–1928) emerged as a powerful force against these injustices. Born in Chempazhanthy near Thiruvananthapuram, he saw firsthand how harshly marginalized groups were treated. With a firm ethical and spiritual commitment, he set out to break down the walls of caste divisions and push for a vision of human equality.

Through his teachings and reforms, Guru called for a universal sense of brotherhood, urging people to look beyond caste and religious differences. His famous statement—“One in kind, one in faith, one in God is man, Of one same womb, one same form, Difference none there is at all”—echoed throughout Kerala and spurred transformative social, cultural, and spiritual movements. Today, Narayana Guru remains an enduring symbol of Kerala’s collective conscience and a guiding light for social reformers throughout India.

Narayana Guru’s social vision centered on a few simple yet profound principles. One of his most famous proclamations, “One Caste, One Religion, One God for All,” reflects his conviction that humans share a fundamental spiritual bond beyond caste, creed, or social class. He believed true spirituality should unite people rather than split them into rigid categories.

Another key aspect of his philosophy was universal brotherhood and religious harmony. Kerala has long been home to multiple faiths—Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and others—so Guru encouraged everyone to recognize the common threads of compassion, love, and moral righteousness that flow through all religious traditions. By seeing these shared values, communities could look beyond doctrinal differences and cooperate for the greater good.

However, dismantling the caste system in a place where social inequalities were reinforced by powerful elites was no easy task. Guru’s approach stood out because he chose peaceful, inclusive methods guided by his spiritual outlook. Instead of resorting to aggression, he relied on philosophical writings, public speeches, and symbolic acts like temple consecrations open to people of all castes. These actions were calculated to challenge societal structures that benefited a select few.

At the same time, Narayana Guru advocated for modernity while keeping a strong connection to cultural heritage. He believed in promoting English education and modern subjects like math and science, seeing them as tools for economic and intellectual upliftment. Yet he was equally passionate about preserving Kerala’s unique traditions, literature, and local arts. In his view, modern progress was only meaningful if it existed alongside ethical and cultural integrity.

This balanced approach—combining modern education, spiritual universality, and cultural preservation—continues to shape Kerala’s social landscape. Narayana Guru’s message was not limited to his generation. It set the stage for a more equitable, forward-looking society that values tradition without being stifled by it.

One of Narayana Guru’s most impactful contributions was his deep commitment to education as a catalyst for social change. Lower-caste communities were often prevented from attending traditional schools, which meant they had limited options for improving their lives. Aware of this, Guru became a trailblazer by setting up schools in various parts of Kerala. These schools were intentionally open to students from every caste, a bold move in a time when exclusionary practices were the norm.

Guru also pushed for a curriculum that went beyond religious or caste-based instruction. He wanted to incorporate modern subjects like science, math, and social studies. His belief was that broadening educational horizons would nurture critical thinking, empower individuals, and ultimately reshape society. At a time when the majority of lower-caste people were illiterate, these initiatives marked a monumental leap forward.

An especially forward-looking aspect of Guru’s educational philosophy was his focus on girls’ education. In a society where women were often confined to domestic roles and seldom granted the same rights as men, he saw education as a key to their emancipation. The schools he established welcomed female students, giving them the chance to develop skills and confidence. Over time, these efforts helped chip away at patriarchal norms that had long held women back.

Another significant step was his decision to make Sanskrit education available to everyone. Traditionally reserved for the upper castes, Sanskrit was seen as the language of scripture and spiritual knowledge. By opening Sanskrit lessons to people from all backgrounds, Guru challenged the long-held belief that only certain groups were worthy of spiritual and philosophical insight.

Moreover, Guru believed in practical skill-building. He encouraged vocational and technical training so that marginalized communities could achieve economic self-reliance. This included teaching crafts and trades that would enable them to find employment outside the limited, caste-dictated jobs they were historically forced into. Many individuals who benefited from this training improved their economic standing, thereby gradually eroding caste-based occupational barriers.

All these educational endeavors were largely carried out under the umbrella of the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana (SNDP) Yogam, which Guru inspired and guided. This organization handled the day-to-day running of schools, mobilized local resources, and lobbied for policy changes. The continued growth of these institutions laid a foundation for lasting social transformation across Kerala.

One of the most dramatic events led by Narayana Guru was the 1888 consecration of a Shiva idol at Aruvippuram. This act went beyond a religious ceremony, as it directly challenged the established norm that only upper-caste priests had the authority to consecrate idols in temples. By placing the idol himself, Guru made it clear that spiritual matters should not be the exclusive right of any one group.

The Aruvippuram episode was only the beginning. In the years that followed, Guru oversaw the consecration of more temples open to people of all castes. This was groundbreaking because lower-caste communities were traditionally banned from even entering temples. By openly inviting everyone to worship, Guru sent a strong signal that faith should unite rather than divide.

What’s more, Guru saw temples not just as places of worship, but also as community hubs. He envisioned them as spaces where people could come together for spiritual growth, cultural gatherings, and even educational programs. Many of these temples included classrooms and meeting halls, serving as a center for literacy campaigns and discussions on social issues. In doing so, Guru effectively turned religious sites into engines for social progress.

Unsurprisingly, sections of orthodox society tried to discredit Guru’s work. They called him a heretic and argued that he was tampering with tradition. But Guru’s moral and spiritual authority, coupled with his calm yet firm approach, won him considerable public support. Over time, this momentum fed into other temple entry movements throughout Kerala. It also influenced legislative changes, including the Temple Entry Proclamation of 1936, which finally granted all Hindus the right to enter temples.

Today, these inclusive temples stand as monuments to Guru’s enduring commitment to equality. They remind us that religious spaces can be powerful symbols for social unity and that change is possible even in the face of fierce resistance.

Though often remembered for his spiritual and educational reforms, Narayana Guru was acutely aware that social equality also depends on economic empowerment. He encouraged marginalized communities to break free from the constraints of traditional caste-based occupations and seek better economic prospects, including entrepreneurship and small-scale business ventures. By supporting and guiding them in these efforts, Guru helped create a climate where individuals from lower-caste backgrounds could explore new ways to earn a living.

At a time when trade and commerce were mostly monopolized by privileged groups, Guru actively spoke out about the importance of opening doors for disadvantaged communities. His followers began to form small businesses and trading networks, challenging the status quo in markets long dominated by upper-caste merchants.

He also placed a strong emphasis on cooperative movements. In this model, small producers and traders pulled their resources together, sharing capital, knowledge, and skills. These cooperatives offered a collective approach to competing with bigger, more established businesses. Such mutual cooperation helped people who previously had very little capital or social influence to stand on their own feet.

Even before phrases like “financial literacy” were commonly used, Guru stressed the importance of managing money wisely. He encouraged saving, thoughtful investing, and steering clear of exploitative lending practices. By promoting these ideas, Guru laid the groundwork for a culture that valued responsible financial habits—an idea that continues to resonate in economic development strategies today.

Ultimately, his vision for economic empowerment revolved around self-reliance. While he understood the power of community and group effort, he also believed that true dignity comes from the ability to stand independently. By offering pathways beyond age-old occupational roles, he struck a blow against the deeply entrenched caste system, showing that social mobility and respect are achievable through economic progress.

Narayana Guru’s fight against untouchability was an essential piece of his broader quest for social justice. In a society where entire groups were labeled “impure,” he vocally and persistently opposed any practice that dehumanized people based on birth. Through his teachings, he made it clear that such discrimination was not only morally wrong but contradicted the very essence of spiritual unity that religions aspire to.

He also encouraged inter-caste marriages, recognizing that dismantling caste divisions had to happen not just in public spaces but within families and social networks as well. This was no small step in a society where marrying outside one’s caste was often met with intense resistance. Nevertheless, these marriages slowly began breaking long-standing barriers, proving that personal relationships can be a powerful force for broader social change.

Guru was ahead of his time in advocating for women’s empowerment. He viewed women’s education as a gateway to broader social equality, but he also fought against oppressive customs like early marriage and the social exclusion of widows. Moreover, he believed in nurturing women’s leadership capacities, encouraging them to participate actively in community decision-making.

Labor rights were another focal point of Guru’s reform efforts. Lower-caste workers were typically confined to menial jobs with little or no pay. By pressing for fair wages and better working conditions, Guru aimed to ensure that economic advancement was shared by all sections of society. His insistence on equality extended to access to public services, such as education, transportation, and common resources like wells and inns.

Above all, Guru sought to instill a sense of dignity in every person. He understood that societal change requires more than just laws and institutions—it also demands a shift in attitudes. Through his open gatherings, spiritual talks, and interactions with people from all walks of life, he steadily cultivated a culture where individuals began seeing each other as equals. This moral transformation was as important as any tangible reform in ending caste-based injustices.

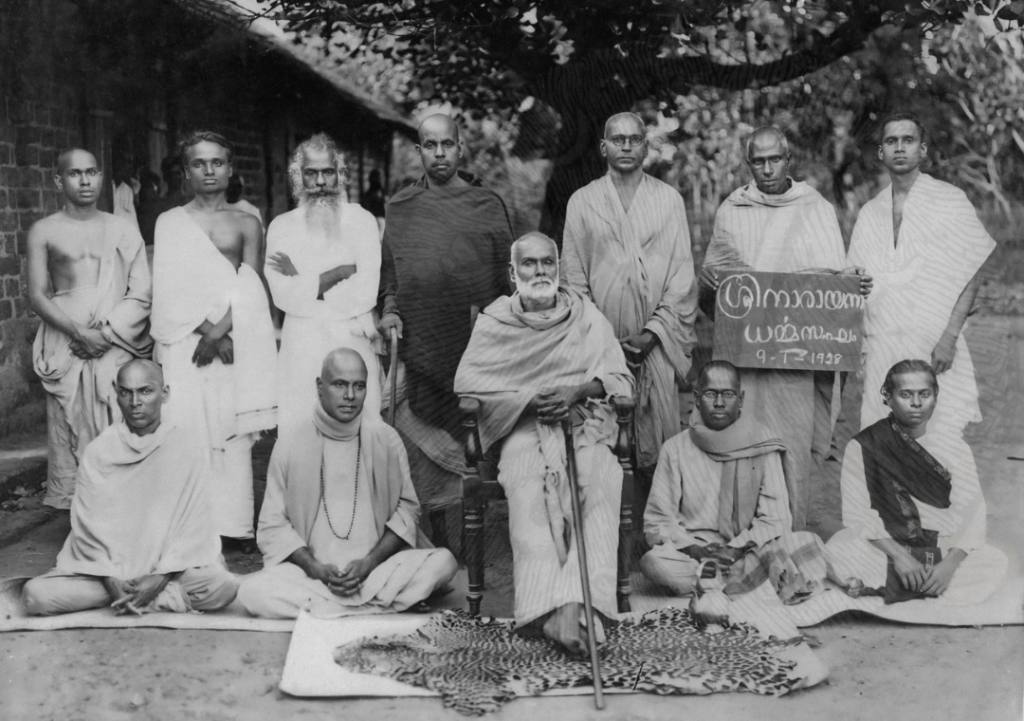

A major turning point in Narayana Guru’s social reform work was the formation of the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana (SNDP) Yogam in 1903. This organization effectively served as the structural backbone for many of his initiatives, coordinating educational programs, economic projects, and social campaigns. It attracted individuals committed to implementing Guru’s teachings on equality, modern education, and self-reliance, forging a cohesive force for change across Kerala.

Alongside the SNDP Yogam, Guru inspired the rise of smaller, localized groups focused on tackling specific social issues. These grassroots organizations brought together local leaders who understood the unique challenges of their communities. Over time, these groups formed a network of reform centers that offered resources like literacy classes, legal aid, and vocational training, all aimed at equipping people to stand on their own.

The impact of this community-driven approach was far-reaching. By engaging people directly in the movement, Guru made them more than just beneficiaries; he turned them into active participants and leaders in their own right. This helped ensure that social change was not a fleeting event but a sustained process embedded in daily life.

Narayana Guru also played a pivotal role in reshaping Kerala’s cultural life. Many of the region’s social customs and ceremonies at the time were laced with caste-based restrictions, reinforcing old hierarchies. Guru challenged these practices by promoting simpler, more inclusive ceremonies for events like marriages and funerals. He stressed that culture should bring people together in celebration, not keep them apart.

However, his stance on tradition was balanced. Rather than dismissing all customs as outdated, he sought to keep the ones that upheld values like unity and compassion. Where a ritual or practice promoted discrimination, he worked to either reform or replace it. This nuanced viewpoint allowed communities to preserve positive elements of their heritage while shedding those that perpetuated inequality.

Guru also recognized the power of the arts to transcend social barriers. He encouraged music, dance, theater, and literature, offering platforms where people from different castes and backgrounds could gather. These cultural events became spaces where art, spirituality, and learning converged, further blurring the lines of social division. Over time, such gatherings contributed to a more open and accepting cultural environment.

This cultural renewal wasn’t just about celebrating the past; it was also about welcoming the future. Guru believed that scientific thought and global perspectives could enrich local traditions rather than threaten them. His inclusive approach to culture helped Kerala incorporate modern ideas without losing its sense of identity.

Narayana Guru’s transformative impact still resonates in Kerala’s social fabric. His efforts to promote education helped raise literacy rates and made formal schooling more accessible to formerly excluded groups. Over the decades, the barriers between castes have continued to erode, thanks in large part to the institutions and reform movements he inspired.

His temple entry campaigns and emphasis on universal spiritual values paved the way for later movements, such as the Vaikom Satyagraha and the 1936 Temple Entry Proclamation, which officially opened Hindu temples to all castes. Numerous social and political leaders have drawn inspiration from Guru’s commitment to non-violent, inclusive reform. His example has guided countless activists—both inside and outside Kerala—in addressing issues of caste discrimination, religious intolerance, and gender inequality.

Even today, the challenges Guru fought against—like unequal social structures and lack of opportunities—exist in many parts of the world. In this sense, his message remains highly relevant. Calls for greater equality, ethical governance, and compassion in public life resonate deeply with his core teachings.

Institutions like the SNDP Yogam continue to operate schools, colleges, and community programs, ensuring that new generations are familiar with Guru’s ideals. Modern interpretations of his work are spread through seminars, publications, and cultural festivals, reminding us that unity in diversity is more than a slogan—it can be a lived reality.

Narayana Guru’s life shows how a single individual, guided by empathy and conviction, can radically transform societal structures. His legacy is a powerful reminder that no matter how entrenched inequality may seem, it can be challenged through peaceful means, persistent education, and unwavering faith in the fundamental unity of all human beings.

Narayana Guru, the patron and lifetime president of the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana (SNDP) Yogam, resigned from the organization in 1916, citing dissatisfaction with its narrow focus and exclusivity. Though the Yogam was initially formed in 1903 to propagate his teachings and ideals, the Guru objected to its constitution defining “community” as limited to Ezhava, Thiya, and Billava groups, instead advocating for a universal human family. Despite his cautions about the adverse effects of such caste-based thinking, the leaders were unwilling to adopt his broader vision. Disheartened by their inability to transcend caste pride and truly align with his liberation movement, the Guru resigned, emphasizing that he belonged to no caste or religion.